Episode 13: Evidence-Based Design in Healthcare with Richard Rucksdashel

Read HKS’ study on Hospital Acoustic

Designing a space that works can be a tough challenge. Designing a healthcare space that works can be near impossible. In the past, the design has been very subjective in nature, and what looks good or works for someone might be the complete opposite for someone else. But, with the rapidly changing landscape of healthcare design and operation, scientific evidence for design is becoming the new standard for providing the best space.

Richard Rucksdashel, Director of Healthcare for HKS Houston is one of the people pushing for a more evidence-based design standard in the healthcare design community. Richard explains, “We think this is where we see us going to best serve our clients. And one of that is in our ability to deliver research that allows our clients to be confident in the decisions that they want to make. So that leads us to be trusted advisors…”

The idea that the best practice for design in a medical facility should be based in the scientific method sounds somewhat obvious, but until recently it has rarely been used, according to Rucksdashel. Fortunately, HKS has devoted a research team to spend countless hours evaluating various design ideas and determine if the data supports those ideas. Richard also praised several of his colleagues who would be considered his competition in also driving design from a scientific point of view. He says that his passion for the patients who come to the facilities that he designs drives him to focus on their well-being, even if the design came from a competitor.

With all the constant change that technology brings to the healthcare industry, HKS is leading the charge through evidence-based design. Richard adds an additional point about what the focus should be for all designers in healthcare, “The thing that really makes that so important is that technology leads to better recovery… And that’s the one thing that you never want to get too far away from.”

Andrew: [00:05]

Welcome to the Privacy Matters Podcast. I’m your host, Andy Vawter.

In this episode, I sit down with an expert in the healthcare design industry. He has over a decade of experience working as an architect in this industry, and he’s a Principal and Director of healthcare for HKS in Houston. His name is Richard Ruskcdashel. Richard worked on some amazing projects for some of the largest medical organizations in the country. He has extensive experience in the field of architecture and design. But what you will quickly hear is how much Richard cares about the patients who come to that hospital. We will talk about how research and data are driving design decisions as well as how the focus on patient healing is changing how we design and build spaces within the healthcare industry. This is a little bit longer episode than usual, but I think you’re really going to enjoy hearing his perspective.

All right, Richard, thanks for being here. I’m excited to have you. So let’s get started. Just tell us your current position here at HKS and what you do and then we’ll kind of go from there.

Richard: [01:14]

I’m a principal at HKS but as far as the firm at large, I’m also one of the Healthcare directors in the Houston office. Houston office has been in place for about five years. We’re coming up on five years in October and before that, it was with HKS and the Dallas office for about 15. So roughly we’ve been with HKS for about 20 years most of my career. I did a little bit of time in another firm between undergrad and graduate school. (Andrew: But basically since you’ve been out of grad school you’ve been with HKS.) I started off in Dallas as a general architect, what HKS calls back in 2000-2001 they had what they called a Cross Training Program. And that allowed for a developing architect or an intern is that’s what we call the architect coming out of school before they’re licensed that gives them the opportunity to be exposed to. I’m working on projects from the beginning to the end from concept all the way through delivery of the project to the client, but cross-training allowed me to learn the ins and outs of projects. (Andrew: How’s that different than somebody else’s experience.) Right. (Andrew: So it sounds unique). The way we talked about HKS and I can’t really speak to other firms but within the industry like most industries, I would suspect you have the potential on a very diverse scope of work to maybe be pigeonholed a little bit. And that’s not always a bad thing but in order for us to be good advocates and trusted advisors for clients it helps that we are well rounded.

So when you start to learn the ins and outs of the process of delivering a project to a client being able to say, I’ve been exposed to what it means to work with a client, to interact with the team earlier in the project and concept and design, being able to take that design work through and make documents and then be a part of the construction process and turning it over to the client really allows for us to have a better perspective. When we started it was called Crush Training program and I did a couple of projects that way and then realized, Hey, you know what I’m not quite as excited about the technical side. I’m maybe a little bit more naturally leaning towards design and planning. So within health care, we have what we call the Medical Planning. Kind of denotes what we actually do is we develop the plan like for those who are not familiar with the architecture. When you look at a floor plan from above and you see the rooms as squares and the doors as quarter circles and you have hallways and like what most people look at when they look at a house plan. That’s kind of what we do we create those spaces. And really what it is taking the design concepts through a couple of phases, actually three phases, Chromatic Design, Design Development, and Construction Documents. What that also means is that you were interacting with the clients. It’s upfront when you’re talking a lot about design concepts and what you think you see wrong with the current state of our institution or the way that you work, the operations of how you work. So being a planner allowed for me to, to really engage with a client when we started making lists of things that they wanted, a new building or what we call program. We identified problems and how we could fix it and it started to develop an architectural response to those issues to make it better environment really got engaged in that part.

Andrew: [05:34]

So over the years, did you find yourself sitting down with the customer? And that probably is different depending on what health care organization you’re talking to. Did you find yourself sitting there and they’re describing the exact same problems that the last one you just finished? And so now you’ve got kind of, you’re in luck. So we’ve just completed something like that.

Richard:

In 20 years, putting those conversations that you start to understand as a building kind of come through a life cycle. In health care, for example, an inpatient tower where you’re checked-in or admitted to a hospital. Inpatient towers in the US are probably 30, 50 years old before they’re turned over. But as we looked at designs that were done in the 70s, 80s, 90s, there was a lot of changes that have happened. So yes, you hear the same things. We need more space, we need more storage, we need to have nurses and patients be able to see each other. We want more of using the outside and in the last probably 10 to 15 years, what we’ve really kind of taken out of the academic arena is that the exterior views of nature access to art that has a natural component to it really do create a more healing apartment. So you hear those same things that really the healthcare environment out of the 60s and 70s didn’t really address you see those needs. And then to counterbalance that, you always have a unique situation where they have a request or insight into what they want to do differently. That’s completely unique and it usually puts a stop at me and you’re like, well, wait a minute. Okay, time out. Help me understand that because that’s not exactly how we’ve heard in the past. And it’s kind of a dynamic that I enjoy kind of have that moment with every client. Where did you stop? You go, huh, I haven’t heard of that before. And you can kind of put that in your database in the back of your mind and try to understand how that might be different.

Andrew: [07:45]

In the end. That’s really why someone would hire an architect, to begin with, is because, I mean, if they’re just wanting to do the exact same thing somebody else did, I’m sure that’s relatively straight forward. But the fact that they can point out something to you that’s unique and say we have this vision to do this or we want, right? We want our people to feel this way when they walk into space. And that’s all of a sudden now it takes somebody with that knowledge and expertise to hear that and then implement that.

Richard:

Yeah. We can easily take a Walmart type of scenario to say every hospital across the United States does the same thing the same way. That’s not really what we’re about. There are institutions that do that well and what do you get out of that is consistency. (Andrew: Same experience regardless of what city you’re in.) Strengthen quality, you know, what you have. A lot of times that’s in a private market or private institution where they do have a business model. So if you want to invest in health care and you find the private institution not public and you want to see revenues that are there. And if you’re a patient, you know exactly what you’re giving, if you’re in Nashville or Las Vegas, you think the same thing. The architecture really is what I would call custom. It gives the ability to influence how we deliver care. And when you talk to people in the health care delivery, whether it’s designing or if it’s on the front lines with nurses and doctors. Oftentimes that’s how they get into the market. No one wakes up as an 18-year-old and says, Hey, you know what, I wanna do. I wanna work in healthcare. Usually, I want to be a doctor so it can help somebody. I’m an architect, goes to school and it’s not the sexiest type of project you want to work on, but you realize in all the types of buildings that you’re going to build healthcare has left you one of the most impact situations. (Andrew: Take me back to, you know, was it high school when you decided you wanted to get into this or were you already in college? You know, so you had to pick a major or out of that work?)

In a lot of ways, it did happen just in a process. I naturally am a drawer left-handed kind of have always been able to see things three-dimensionally. I was thinking about this when we talked about doing a podcast back in Texas in the 80s when I was in elementary school and junior high and going into the 90s and the high school Texas had what was called SRA, there were standardized tests. And one of the portions of the test was trying to imagine the 3D Tetris shape. And they would say, okay, if you’re rotated this way and that way, what would that shape look like? And you had to pick from A, B through D and it was a test sampling that would take 25 minutes. I would get done at 10 minutes and put my pencil down. You know, when you’re used to sitting on those rows of tables, the space between each other I’d put my pencil down, I looked up and I was the only one with my head up and I’d wait 10 minutes before the next person would have their head up. And then I didn’t understand it at the time, but my ability to process shapes and forms and dimensions and that sort of thing was maybe a little bit got God-given. I won an art contest in the second grade to bookmark for my imagery school. And my mom was like, Hmm, maybe we need to look into art for you. By the time I was in fifth grade, I went to a city-wide competition here in Houston and was born and raised here.

So I realized that drawing was a natural expression for me and it’s something I do in my free time. Even to this day, I have a sketchbook. It’s probably my backpack over here. I have a sketchbook. So the way I think, the way I communicate a lot of times comes through and drawing so it was natural. I got to high school and someone had told me early on architecture was a little bit rough of a profession. In other words, it was kind of hard to make a good living. So my dad was an accountant. You know, kind of based on the realities of business. He was a businessman worked in downtown Houston and he said, Hey, you know, you might want to look into engineering as well. That’s a really strong profession. You can most likely get a job. And I kinda liked that idea. So as I got into high school, started excelling in Calculus and Physics and sit for the AP exams and got some credits and ended up going to A&M within the engineering and school. Turns out while I was pretty good at it, I was not as good as others. And after about three semesters they sent me down and said, Hey we think you might want to look at some other avenues. (Andrew: The nice way of saying, you’re not gonna make it). Yeah, very calming. You’re out. And my parents are great in this and ended up being one of those kinds of pivotal points in my life. They had stayed away from the kind of giving their 2 cents when they didn’t think I wanted to hear it.

But as soon as I took one class in architecture and within probably two hours of that first class, I was like, why have I not done this before? Ended up at the Dean’s list after like the first semester, maybe through undergrad architecture was in three years and not because of anything that I did. I think it was just where I was supposed to be all along. So at that point, I got into A&M School of Architecture, found out that it was a what’s called four years undergrad, two years graduate school in order to get a professional degree in architecture and that’s a requirement. In order for you to become an architect, you have to have a professional degree in architecture. So that meant all of a sudden I had to go to grad school, I was like, wow, I never really consider myself an academic.

Now, I’m looking at grad school as well and got involved with other clubs and extracurricular activities at Texas A&M ended up doing a quick stent at an architecture company in Dallas. And ended up coming back to A&M for grad school. So I was agreeing what’s called a bachelor’s degree in environmental design from Texas and then went back for a master of architecture. And at that time A&M was one of two schools in the United States that had a focus on healthcare. I took a junior level studio undergrad that was healthcare-focused and did an outpatient clinic for Presbyterian hospital which is now THR in Dallas. We designed the outpatient clinic in Coppell, Texas. It was the most I’d ever done a project as far as planning and really liked that. I had to think about how not only a patient but a family member, visitor but as well as staff, nurses and doctors would all have to interact in the building. I’d have to understand the flows, how it all works and try to put that together and be somewhat successful. So I ended up working in healthcare for that company in between undergrad and grad school. And then came back to A&M and got what’s called a Certificate of Healthcare. It’s just kind of the focus. (Andrew: That was where you understood that might be the niche that you wanted to.) So yeah, again, it was kind of why would anybody go into the healthcare? Well, there were some complexities to it. I remember having the dinner with my parents when I was just going into grad school and I had to make a very tenuous decision on whether or not I was going to go to Italy, study abroad for a semester or submit for a health care education grant and actually went for the grant and gave up going to Italy.

And while healthcare has been incredibly good to me, I still regret not going to Italy on the study abroad. So I kinda made that decision. You know, talking to my parents and my dad said, Hey look, we know there’s going to be health care as baby boomers get to the age where they need it and we’re right smack in the middle of the course. And if you can design a hospital, you can design anything else. So why don’t you try it to see what happens? Well, 25 years later I’m directing healthcare here in Houston. (Andrew: So kind of worked out.) It kind of worked out. Yeah, I’d probably go to Italy at some point to like, that’s probably something I can do here, but that on the schedule. Exactly. You know, and that can leads to, to make it full circle. Being here in Houston was very intentional. You know, I left in 1994 to go to school. I’m thinking I would never come back to Houston. The fact that I joked about it you know, why would they come back to the city with large amounts of traffic cause humidity’s outrageous, especially in August. Why would I ever come back here? Well, it turns out that five miles down the road from our office here is the largest medical center in the world. I’ve got five major academic medical centers that really create an environment that’s unique. Healthcare, medical planner and my background and medical planning and now and project management and directing of the healthcare practice. We get to do things here on the design side and interact with clients and what they’re trying to do in the way they work with each other that few others get to do around the country.

In fact, a lot of times we’ve had international entities come in, meet with us, talk about what’s going on in the medical center, and then we’ll go down there and walk around and kind of demonstrate how they compete when it’s helpful, how they collaborate when it’s needed and the options that patients have. You know, I think that’s one thing that we’ll see in the next decade or probably the next generation is that hopefully, we see healthcare respond to patient’s needs on a more personal level. We’ll probably get into that a little bit later.

Andrew: [18:55]

Absolutely. We had talked about before we got on here that you said one of the things that HKS is doing a lot of and really trying to pioneer is this idea of evidence-based design. Yes. Could you tell us what that is and then kind of go into what you guys are doing to make that a reality?

Richard:

Sure. It’s a very fancy term or phrase for providing scientific backing to design decisions. And that might sound intuitive, but up until in the last 20 years or so it was not always used. And I wouldn’t say that HKS is necessarily leaving. We are, we could. We’re infested. I don’t want to diminish what our industries the great thing about what I see is that architects are passionate and the people we compete against are incredibly talented. We talk daily about how we can maintain a stance of who we are how we lead the industry. And that’s not to say that we’re the only ones doing it. You know, we learned from our competitors as much as anyone else. I think fortunately we have a desire in, and maybe sometimes it’s resources to really jump in and say, look, we’re committed to this. We think this is where we see us going to best serve our clients. And one of that is in our ability to deliver research that allows our clients to be confident in the decisions that they want to make. So that leads us to be trusted advisors that we advised with influence. In other words, when we tell a client, Hey, you know inpatient design is telling us that the taught room and the patient room needs to be here. Or as you look at the things, the factors that you take into consideration this is what science is telling us. It is a good old fashioned science fair scientific model. How about the hypothesis, do the research graph the outcome and then provides your results. And we’re very fortunate to have a research group led by a PhD by the name of Pauline Nanda, who’s in our Detroit office now.

Although we consider her to live here for quite a while. Her husband worked at MD Anderson. She leads our healthcare research group. And for the past decade or so, it’s really a lot of health care specifically to really have a foundation that we’ve talked about even in the academic arena. As I was in school, we talked about making decisions based on what we know and not what we think because the design is subjective in a lot of ways. So I can tell you, look, I really think that this color is the best for this room. And you can tell me, I totally disagree but if I came to you and said, how about I show your white paper of scientists that did research over five years that said that 75% of the population thinks that this color is the best and it makes them feel a certain way. You would sit back, you’re unsure and go, okay, you know, we take the subjectiveness.

Andrew: [22:28]

So you had this research team. Do people from your team give them kind of topics to look into? Is there a lot of back and forth interaction? So you’re looking for help as far as I need evidence to know what to do here.

Richard: [22:42]

Yeah, absolutely. Integration into the project teams is instrumental. In fact, as we propose on projects, we put their names and their resumes in and I like it cause it has a PhD with a whole bunch of acronym, a bunch of letters behind it. Yeah. Because of this, this group is just phenomenal. And what he and others have done and been incredible that integrating themselves naturally into our project teams. So we have junior level job captains or project architects that are taking time within a project to look into the research.

So we start going into databases. We started pulling on resources and compiling information. In fact, when we talked about doing this podcast, I shot off an email, said, Hey, let’s talk about privacy acoustics in a healthcare environment. And boom, a week later I’ve got a report back. I’m like, guys, y’all are awesome. You know, it’s not that I’m surprised by this. It’s just, you know that’s exactly what we need. Everyone’s human. And as we looked at healthcare, it’s way too complex to think, well, I’m going to have all that in my head. You know, even after 20 years, the one thing I know is that the firms that are going in this industry, the more I have to learn.

Andrew: [24:04]

Well, the more it changes. I mean, what are some of the biggest changes you’ve seen in the healthcare industry, let’s say in the last five to 10 years?

Richard:

Wow. Where do I start? (Andrew: Let’s start with a shortlist.) Yeah. I think to be actually accurate the biggest changes would probably be on the technology side. The thing that really makes that so important is that technology leads to better recovery at least the healing. And that’s the one thing that you never want to get too far away from in the age of talking about how healthcare is being dealt within the US and the politics of who’s resulted for it, who has the right to access to healthcare. All that to be said when it really comes down to it on a daily basis. If you’re not looking at what does it mean to heal a patient and get them back home? You know, we don’t want to go too far into, we’ll talk about healthcare without realizing that healthcare is unique in little ways, that a lot of times you never intend to go to a hospital. You don’t even really intend to go to an outpatient setting. Now from a prevention standpoint, you need to intend to go to the doctor. But that’s another trend in itself is the idea that we focused more on prevention instead of reaction, right? So the treatments and that’s really making throwing, making a stance.

Andrew: [25:44]

What do you think is driving that? Is that the health insurance companies pushing it to hopefully lower costs because their patients are better? Or is it ad campaigns by the ad council?

Richard:

If you get a good amount of it. How much do we put the chicken or the egg first here? I do think that there’s a reality of education, but it’s kinda come to a head, right? As we have access to information on the internet for all the bad things that come out, even, especially on the healthcare side, you know, the rule of thumb is when you have the symptom, don’t ever go to the internet, right?

Because you’re going to end up having some sort of. (Andrew: A meme that I had a cough and now I have the bird flu.) You know, that’s what I have according to the symptoms. But as people realize there is some foundation to healthy living to prevention. We’re starting to see the influences of the market to that insurance promotes prevention, right? You get the reimbursements that you need to set up an environment and hospitals that have traditionally been all about treatments, right? You’re sick. Then you go to the hospital and they try to get you better seeking home. They’re realizing that there is an advantage not only financial but operational advantage to having a relationship with a patient or a person at the pond, not even the patient having a relationship with a person in the community before they’re sick to say, Hey, look, if we can help you understand how to eat, what sort of diet to have so that you’re not coming in 15 years with a diagnosis of prediabetes or elevated cholesterol, you’re going to be better for it.

We’re going to have a financial model that probably works now. And we, therefore, have a relationship where you can come to us, you’re a trusted healthcare provider and it’s all about keeping them out of the institution. I think that’s really where we’d like to see things go. Because by the time you were in the hospital you know, you’re reacting a lot of ways. So there’s a trend towards really, you know, it’s been talked about for 20 years, but probably in the last five years we’ve seen, well, maybe, maybe 10 years, we’ve seen that even these hospitals, for example, five major medical centers in the Texas Medical Center, Memorial Hermann Methodist, Texas Children’s, St Louis, MD Anderson, you’ve seen them spread out and put outpatient in even some inpatient hospitals in the community. They go out to the suburbs in the original locations to say, we’re going to give you access to health care. So that you’re not waiting, you’re not afraid of coming to a big hospital in order to take care of that thing that’s been bothering you for five years. We’re going to give you access. We’re going to become part of the community too, you know that’s really a macro trend that we’re seeing on that level.

Andrew: [29:08]

Obviously, there’s a need for continued advancement in some of this. So what is one of the areas that you feel you know, maybe hasn’t changed yet, but you’d like to see change and you can be diplomatic?

Richard:

I really think that we are somewhat in the infancy stage of creating an environment and I don’t want this to be an architect talking about design, right? It’s the idea that a monkey will tell you to eat bananas. But if we have the ability to demonstrate that it had been an environment in a way that it’s created around the situation for a person, whether or not it’s a patient or staff or physician. And there was an impact for that patient is healing quicker and can go home or the staff is happier and you have less turnover. If we can greet the environment I do think and looking long term, I think there’s a lot of ways to grow. Pharmaceuticals, they’re getting better and better, right? There are magic pills sometimes these days and the real growth places within the healthcare industry are what we’re calling personalized medicine. In other words, Andy, this is your DNA. This is who you are. These are what your body, here’s the information your body’s telling us. We’re not going to give you Tylenol for your pain. We’re going to give you kind of that direct shot of this treatment plan for you because this is what your body will respond to based exactly. And you that’s not necessarily a generic conversation. That’s you’ve got this disease of we’re going to find a way to treat the progression of this disease for you at this time. We see in the cancer environment and ecology where they’re able to understand what that tumor cell is doing, how is it kind of mutated from a normal cell? How is it responding?

How robust is that cell? How resistant is it to treatment. And you kind of fine-tune the care method right then and make the perfect cocktail of, yeah, it’s personalized. It’s understanding how to best treat that patient. And not to quote the $6 million man, but we now have the technology or we’re starting to and that’s where we see a lot of the market is going before it was okay, hook all these patients up to the same thing in church and just see for lucky now it’s like, Hey, this is the person, this is who he or she has and we’ll see where it goes.

Andrew: [32:23]

So you mentioned earlier that your team sent you acoustics data upon request which is fantastic. What are some of the issues that you’re seeing when it relates to acoustic? Obviously, that’s what we do. So, I’m always interested to hear from someone who is as plugged into a specific industry as you are. How is that affecting healing? How is that affecting the relationship between the hospital and the patient or the hospital and their investors? What are you seeing?

Richard:

We’re seeing most definitely that the acoustics in an environment is providing a psychological and physiological impact on patients. There was an article I read not too long ago that said that the noise level within the ICU or intensive care unit is similar to going to the concert. And some degrees it’s somewhere about the 95 testable levels. If we were to set up this room this podcast would be very different. And it kind of stops you for a second, there’s no way it’s a closed environment. It’s a four of a billion. How can that level be that high? Well, if you consider the materials that you have on the floor and the walls and the ceiling and what’s required from a cleanability from an infection, important hard. (Andrew: Wipeable, bleached surfaces are required.)

Yeah. And penetrable is really the term that comes to mind. Plus the fact that in order for nurses to monitor traditionally you’re connected to a physio monitor that beeps alarms. Since all sorts of auditory signals to the staff and to the physicians. So if you look down the list of what’s really going on that’s not too surprising but if we look at the fact that alone has the ability to affect your ability to heal what we’re finding is that we’re looking for subtle ways to make changes. A lot of times we’re looking at turning the monitors off and providing secondary like a flashing light. One of the things was really interesting is the role of haptics, which is the technology of vibrations, which smartphones are really true innovator rough. You know we’ve gotten to a point now where you can tell who’s calling you by the different vibrations you have on your phone or your notifications. It’s just a little different. I know when I get a weather update because it’s just a little bit different than everything else, even if it’s in my pocket. So you’re looking at lights different monitoring where we have the technology to send an alarm to a certain location at a certain computer. You know, those sorts of things. Traditionally within health care, acoustics is only dealt with in the ceiling. You’ve got the acoustical ceiling tiles are what I call ACT. And they’re made of materials that allow for sound to come in and become lost in the baffles of the material and that was about it. I do think that’s where we probably need to look at options that allow for infection control to be kept in a place that allows for sound deadening materials to make a difference.

You know, form fall is a function to a certain degree. But within an ICU environment or inpatient environment function has, you don’t really have a choice. So the real challenge and I think that’s one of the things that I really enjoy is you don’t really have a clean slate within the health care. You have to deal with operations of space, you have to deal with the function of the space, yet we’re still challenged to create a form or design. That makes sense. So that’s really the challenge for us and the next generation is how do we allow for an environment that not only is visually healing, environmental healing, but also acoustically healing. So I think there’s a huge market to understand that. And what the options are working with infection control directors on hospitals to say, okay, we have options, where can we work in? We work on it.

Andrew: [37:10]

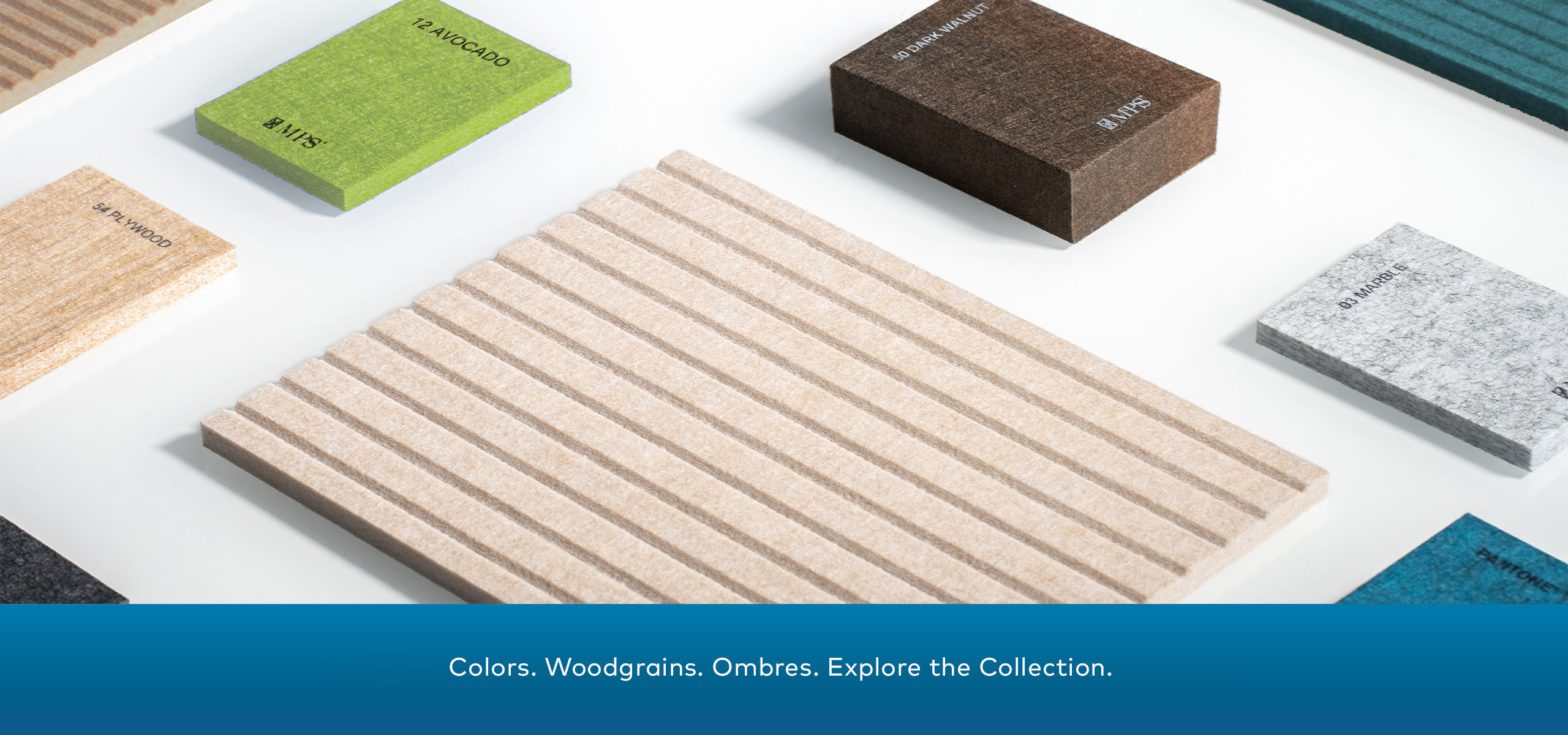

So where does that testing take place? Obviously, the manufacturers of the material are doing it, but there’s gotta be a handshake there at some point where the director of infection control at the hospital working possibly with an architect firm. Determined like does a field test of the material. Is that kind of the playbook?

Richard:

Yeah. Mockups that are the best way to go about it. And if we’re really lucky, we’ll have them a client or a hospital administration, we’ll donate a room and say, Hey, look, we’re going to use this room yet. Let’s go ahead and test a foreign material. You know, a great example is a vinyl. The in sheet vinyl, which has been the mainstay of healthcare for me yet we’re seeing rubber 2 millimeters, 3-millimeter rubber comes into play, not only from acoustics and look but also the impact on all people’s feet, right? So if you are nurses been on their feet for eight to 12 hours, it has an impact. So there’s always an opportunity to test these materials, but within healthcare, they’re never coming out of their environment right? We always go to them. They’re busy. So we take some materials to them, we test them in the spaces that we have and, and work from there.

Andrew: [38:42]

Okay. That’s really interesting. What are some of the other ways you stay on top of current trends? Obviously mockups and just kind of that, but is there another way that you do it or other ways you do it?

Richard:

So I think interacting with professionals in the industry is critical. Going to the conferences, listening to other people are doing healthcare changes. It’s like technology, right? You know, we’re going up, you buy a TV and in 1975 and then 1995, you had the sort of the TV out because you get in pull up the components in the back of the TV within the healthcare. Every six months technology is replacing itself. And I see in six months rather arbitrarily, I’ll give a more definitive direction in that diagnostic imaging arsenide or radiology society of North America meets in Chicago. Every December, a radiologist from around the country go and look at what the vendors are providing. And depending on where we are in the design process, we will have a cat scan or a CT machine or an external machine or angiography or MRI. If we go past December, odds are when we get back on the project in January, we’ll be updating that piece of equipment. Just based on what the radiologists come back from seeing what the vendors are able to do. Whether or not that’s new technologies that allow for them to interface with a unit better or if we’re talking about CTS, it’s more slices or better resolution or quicker download or interactive integrative relationships between two pieces of software.

(Andrew: They’re going to get it to where it’s like, Alexa, turn on the CT scan). You know, that can be a completely different podcast, to be honest with you. Is what we expect from the commercial market or retail market. Right? When we walk into the store, we expect that we can give that device, we can connect it to everything we have and we can pay for it with our phones and we’re done. We walk out a receipt is emailed to us. The number of times that I’ve talked with users staff, physicians, nurses, administrators, and they tell us we can’t do that because software A does not talk with software B. And as a result, they have to behind the scenes duplicate information. Put it into both systems or the patient or family has to provide their information, two or three times at the same visit. And you’re wondering, wait a minute, I just bought a car on my phone. I’m looking on a website and it can be delivered to me. There’s my weather app, right? There you go. It can be delivered to me. Why is it for one appointment? I have to go to two different places, fill out six sheets of paperwork, get a hand cramp from having to write this information. Why is it that I’m not able to get on my phone the day before? Give them my information, that sort of thing. So it opens that direction.

Andrew: [42:04]

I think we just stumbled across one of my questions was what makes your job frustrating?

Richard:

So that you know, I was chewing on that a little bit. I think I would be a little bit remiss to say that the use of reimbursements with health care insurance is one of those things that I think is a little frustrating.

If you’re not careful and you don’t understand how a hospital delivers care you would think of that the way that they’re reimbursed drives everything. Because it does have that potential because the way that they set up how they’re going to spend their money is based on how much and what the guarantee is of them getting paid by the insurance company. Well if you look at what the priorities are insurance has some additional priorities on the side. I don’t want to demonize them. The value that the brain really can’t be underestimated. But when you’re looking at, again, going back to that corner central focus of taking care of the patients when they tell you, no, we’re not going to do that scan or not provide this sort of treatment because it costs too much. Somewhat upper down the line won’t be able to get what they need and it’s at the sacrifice of the health of the patient. That’s a frustration, right? it goes back to what rights you have as a patient. What can you expect from the greatest country in the world? But one of the things that we’ve talked about recently, we’ve had some people within HKS go to a conference here for ACHA, American Culture of Healthcare Architects. And they said, well, we spend the most on healthcare. We are not leading the industry and delivering of healthcare. So a return on investment is not happening. That’s really a frustration. It’s not necessarily how insurance is working. It’s the idea that in some way shape or form we’re not doing the best job, are not as efficient as we need to be. And the question is how has that, and ultimately how do we fix it? I’m a big proponent for capitalism. One because we’re inherently motivated to be as efficient as possible because of the return we get. And we’re in this industry because we want to do something good. We want to make sure that other people are healed and can you go back home? But we’re driven to do that ultimately only because we can do our jobs, we can go home, we can be with our families. I can wake up tomorrow energetic and ready to come back into the same place.

Andrew: [45:26]

It’s excellent. So if you had a magic wand and could just fix, let’s just pick one thing that would kind of, and it can be either healthcare in general or specifically healthcare architecture that you deal with. What would that be?

Richard:

I don’t want to get into architecture. I’ve spent so much on healthcare. I feel like that’s probably the only place that I would feel comfortable talking to. We’ve kind of alluded to it. Oftentimes patients feel like they’ve become part of the cog. There is another component that’s being shuffled in, being brought in, being sent through a process or a system. Again, spit out the other side. The ability to provide the dignity, the respect or the perception of those things. Within the health care process where you don’t feel like a doctor has to meet the quota within the hour or so. He’s gonna see me for five minutes this hour and I really questioned whether or not that’s enough time to identify what I really mean. And then to be sent to a hospital and you get pushed through an imaging department or even a worst-case scenario, you have to go to the emergency department and you’re there for 3 to 4 hours. I heard a statistic that people think on average that someone ends up waiting in the ER waiting room for three hours.

Well, in reality, we see hospitals making changes to that by introducing urgent care redneck store with only like, you know, if you’ve got a beasting, let’s go to urgent care. Right. You know, if you have a piece of muddled stuck in your arm now going to nurse education knowledge, I don’t think so. The find a way to make a person feel like they’re valued even when they’ve had to stop everything they’re doing. Put a whole lot on everything and try to take care of something that they’re dealing with and it’s always at the most an opportunity of course. Right. To have them understand that. This is a big institution with all the technology in the world that you’re not just another number, you’re not in the DMV one and you’re pulling one of the tags and you’re now number 83.

Andrew: [48:01]

Well, I think it’s really interesting that was your answer just because when you think about it, I mean, you’re an architect, so you build spaces and yet if you could fix anything, it’s going to be what you could do to make the patient experience better. So, that’s my plug for you and HKS, right? Is obviously if you’re a medical facility, a hospital, and you’re looking to work with somebody on design the right space, I find a lot of confidence in the fact that if your architect is passionate about what you just talked about, passionate about the patient experience and the healing of the patient and how to treat them as an individual that then you’re going to design a space and you’re gonna partner with a hospital to a level that we can say maybe the competition is as well, but it’s at least refreshing to know that at you are, and then your organization is. So then hopefully you’re gonna be able to help create that space that helps them deliver that experience.

Richard:

And that’s been one of the things that I’ve loved about being a part of this office. So I came from Dallas for those who don’t know HKS corporate offices, doubt as to where we have, you know, at this point, probably 7 to 800 employees. And we decided to open offices in Houston 2013 and actually did it in 2014 and we moved down. The really interesting thing for me, it was not the reality of opening a new office, although that can be fairly dynamic and fun. It was being what I would consider the front line of client relationships. The idea that I was five miles from my clients that at any given time where they could pick up the phone and call us and say, Hey, we have an issue with this design element. We’re curious on your perspective. And that’s one thing that, you know, to speak to the dynamics of being an architect in the medical world. Oftentimes, tell people on the architects of the doctors and a doctor to the architects. So as an architecture that might have a background in and construction where they know the nuances of how to put a brick wall assembly together and how to do flashing with windows systems and make sure that we have moisture being whipped out of the building. And they sit down with me for a drink. Oftentimes we’re not talking about the same thing we’ll find common ground as is, you know, you do with anyone in your own industry. But I find myself relating to our clients in a way that the best thing I can do with understands as much as possible what they do, why they’re driven to do, how they work.

So I’ve got to understand what it means for a nurse to try to deliver care. And a lot of times that’s not very interesting. The fact within healthcare it can get gross the number of times we’ve talked about the sole environment, right? Right. So sole in health care just means that it’s a dirty part, right? It’s how do you take care of linens that are not in great condition because the patient isn’t getting out of bed? How do you deal with going to the bathroom? You know, how do you get all those things that were so living that living those realities for the sake of also finding a way for someone that might not have made it otherwise can end up coming out of there.

Andrew: [51:42]

But just an interesting take on the whole thing because you’re obviously an expert in architecture and in design and in building function and form and all that. But then you’ve got to take that extra step and say, I’ve got to put myself in the shoes of a nurse and a doctor. And you know, that’s the most important part about what you do is it’s interesting. It’s almost like the actual way it’s built or designed is just a secondary added function right to the overall.

Richard:

You’re right. A lot of times the client knows that we’re needed. Oftentimes it’s a conversation about code requirements. What are we allowed to do here? What are you seeing? How do we make sure we’re getting the most out of a design opportunity? So we do come in and they turned on us and say, look, we don’t know what the state or the federal government is telling us we’re allowed to do. You know, if we don’t do this, can we do this? Or you know, if we knocked on this wall, what happens? Well, according to code if you do that, we’ve got to take your drawing to the state reviews it. And by the way, you’re going to have to update this space and spend more money. So those are always conversations is making sure that we keep the client informed of the impact on costs and schedule. That’s given and that’s something we take very serious but when you come down to the heart of the matter is always even if we’re working with facilities guys, maintenance guys, engineers that make sure that the AC is pumping 65 degrees into it or they take pride in going home and making sure I do my job. So that surgeon up on the second level could make sure that person has a new hip.

Andrew: [53:36]

Yeah. And saves lives. All right, so we’re going to close this. I’ve got two kinds of personal questions to ask you. Okay. What’s your favorite thing to do when you’re not at work?

Richard:

So I have a 12-year-old and a 10-year-old. My 12-year-old is gifted with the ability to sing. And I love to hear her saying they’re out of town right now. My wife took a video of her singing a hymnal song in the middle of the church in Minnesota and I get to see that last night. I love to hear her sing. My son is 10 and he plays baseball. I’ll have to watch him play baseball. It’s the most nerve-wracking thing. You can do. Be a father watching your children perform and try to do their best. But if it’s those types of things that pull me away from the office with vigor. It’s making tracks get to the game on time. I love watching them do stuff. I also draw a lot. When my wife and I first got married I had a sketchbook with me at church. And during the sermon, I had my head down and I was drawing and we got the name of the church walking out the car and she goes, what? What were you doing? (Andrew: Why aren’t you paying attention?) Right. Why were you not listening? Oh, you okay. As an adult, I’ve come to understand, I process information differently maybe than some people. I’ve come to be able to understand that by me drawing. I listen actively. It keeps me engaged. That’s a professional advantage but it’s also just who I am. It’s who God made me be and that includes free time.

I was in the UK for a conference back in June. I had one day off in a matter of 10 days and I was in London. We come through London to do a tour of the proton center that the NHS was doing in London. It just finished one in Manchester. And I pulled up my sketchbook, dropped it in my backpack and went to see. It was a weekend to the color guard change in one that tried to catch me in the bat with a little bit of delight and then spent the rest of the day in Westminster and in St. Paul and the Tate modern and just drawing the environment. When I don’t have anything else, you know, requiring my time, I will oftentimes pointless get spoken, find something’s wrong.

Andrew: [56:34]

Then obviously this last question, if you had all the money in the world, what would you do? We already know it’d be going to Italy. That would be rather than that, right? But what else? What else?

Richard:

I would probably say travel. I grew up in a family that loves history. We love experiences and we’re always on the go and that included vacations. So between the ages of 4 and 14, I went to all 50 States. And that experience exposed me to all sorts of different people, different environments. I can tell you the things I love most about America. People like all the places you’ve been to. What did you like the best? Like about, that’s a really hard question, but personally, I love the Grand Tetons in Wyoming, spin forced in Washington DC, in Juneau Alaska, depending on what year it was. But traveling exposes you to the wonders of the world, the differences of culture. It shows how different people live, different priorities that people have. I’ve been lucky enough to work on projects all over the world as well. I looked in London for five months when I was a young architect. And living in London as a Texan is a little bit of culture shock, right? Because here in Texas, what you do as an adult or a married man is you got to work. You get in your car or your big truck and you drive on freeways and you go to your house and you’re at home and you see friends by inviting them over for dinner or some sort of event. But your home is your personal space. It’s where you spend most of your time away from the office. In London, you go to a pub, right? Rent or buying a home in London, it’s too expensive. So you live in a little bitty flat. So you spend your social time in a pub. Well, you also have a beer, you have a plate so I got to experience that. So just the realities of what it means to travel and to see what other people doing are amazing. And if I have the money to do that, I’d probably do that in sketch everything.

Andrew: [59:04]

The sketch, everything you saw. There you go. That sounds perfect. Richard, I really appreciate you spending time with us and I think you clearly show your passion for what you do. That’s evident. So thank you.

Richard:

Thanks. I appreciate it.